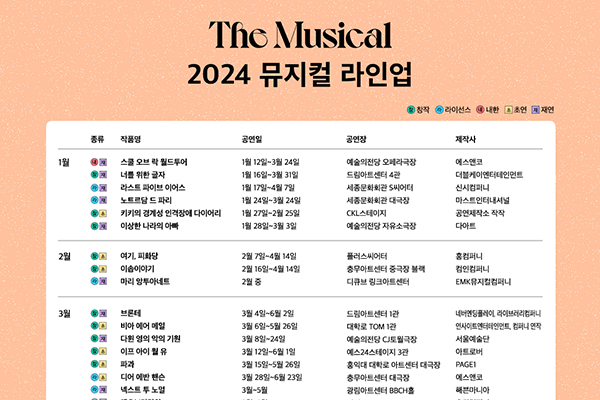

탄탄한 대본과 뛰어난 만듦새를 인정받아 빠른 속도로 세계를 향해 뻗어나가고 있는 K-뮤지컬. 이러한 흐름에 발맞춰, 더뮤지컬이 6, 7월 두 달에 걸쳐 한국 뮤지컬의 해외 시장 진출 현황과 글로벌 뮤지컬 시장의 흐름을 들여다봅니다.

지난 11월 제 뉴스레터인 『Jaques』에 "K-뮤지컬이 브로드웨이를 점령하다"라는 헤드라인을 썼을 때 이렇게 빨리 상황이 진전될 줄은 몰랐습니다. 당시에도 이미 한국의 활기찬 뮤지컬 산업이 국제적으로 큰 영향을 미칠 준비가 되어 있다는 것은 분명했지만, 아홉 달 만에 한국의 브로드웨이 물결이 시작될 줄은 예상하지 못했습니다. 그 글을 쓴 후, 오디컴퍼니의 신춘수 프로듀서가 제작한 영어 뮤지컬인 <위대한 개츠비>가 브로드웨이에서 공연됐습니다. 이 작품은 지난 4월에 개막하여 그 이후 거의 매주 100만 달러 이상의 수익을 올리고 있습니다. 그 다음 달에는 한국 작가와 미국 작곡가가 만든 뮤지컬 < Maybe Happy Ending >(한국명 <어쩌면 해피엔딩>)이 에미상 수상자인 대런 크리스가 주연으로 출연하는 영어 버전으로 브로드웨이에서 올해 가을 공연할 것이라고 발표했습니다.

시기적절하게도, 지난 6월 저는 서울에서 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 직접 볼 기회를 가지게 되었습니다. 예술경영지원센터(KAMS)가 주최한 K-뮤지컬 국제마켓에 참여한 것입니다. 올해는 8개국의 창작자, 프로듀서, 관계자, 기자들이 참석하여 세계 공연 시장에 대한 강연과 패널 토론을 진행하고, 해외 시장 진출을 위해 노력하는 창작진, 프로듀서의 이야기를 들어보는 것은 물론, 한국 뮤지컬 관계자들과 일대일로 만나는 기회를 가졌습니다. 또, 한국 뮤지컬 여덟 작품의 쇼케이스 공연이 펼쳐졌습니다. 저는 브로드웨이에 대해 20년 이상 글을 써 온 뉴욕 기반의 저널리스트로서 미국 극장 비즈니스의 현재 동향과 한국 산업과 브로드웨이 간의 파트너십이 어떻게 확장될 수 있을지에 대해 발표해 달라는 요청을 받아 무대에 섰습니다.

서울을 처음 방문한 저에게 이 컨퍼런스는 매력적인 경험이었습니다. 국제 협력의 가능성을 일깨워 줬을 뿐만 아니라, 우리가 얼마나 많은 공통점을 가지고 있는지, 또 우리가 문화적, 창의적, 경제적으로 얼마나 다른지에 대한 깨달음을 주었습니다. 컨퍼런스가 끝난 후 저는 서울에 머물면서 주목할 만한 한국 뮤지컬인 <프랑켄슈타인>과 <어쩌면 해피엔딩>을 관람했습니다. 이번 한국 방문을 통해 한국 뮤지컬 시장이 브로드웨이와 어떻게 관련이 있는지를 이해하는 데 도움이 되는 유익한 정보를 얻을 수 있었습니다. 이번 여행에서 얻은 통찰을 몇 가지 소개하겠습니다.

1. 한국 뮤지컬 시장은 이미 전 세계적으로 성장하고 있다.

컨퍼런스 발표에서 저는 한국 뮤지컬 산업이 전 세계적인 영향력을 키우고, <기생충>, <오징어 게임>, BTS와 같은 성공을 거둘 수 있는 방법에 대한 생각을 말해달라는 요청을 받았습니다. 첫 번째로 말하고 싶은 것은 ‘이미 일어나고 있는 일’이라는 겁니다. <위대한 개츠비>는 한국 뮤지컬 산업의 브로드웨이 관심도를 높이고 한국 공연 관계자들의 야망을 높이는 데 큰 영향을 끼쳤습니다. 그리고 2016년 서울에서 초연되어 현재 다시 공연 중인 <어쩌면 해피엔딩>이 있습니다. <위대한 개츠비>가 비즈니스 측면에서 큰 진전을 보였다면, <어쩌면 해피엔딩>은 한국과 미국의 예술적 감각을 결합한 '크로스 컬처 창작팀'의 창작물로서 중요한 의미를 가집니다. 이 뮤지컬이 브로드웨이에서 성공한다면 미국 공연 산업에서 한국의 작품과 아티스트에게 관심을 가질 사람이 많이 생길 것입니다.

이와 같은 작품의 가장 큰 과제 중 하나는 국경을 넘어 작품이 지닌 이야기를 전할 수 있는 방법을 찾는 것입니다. 각 문화는 작품에 대해 서로 다른 기대를 가지고 있습니다. 뉴욕에서 인터뷰한 한 젊은 한국계 미국인 연출가는 미국 관객들은 플롯이 중심이 되는, 영웅의 여정을 강조하는 작품을 선호하는 반면, 한국 관객들은 감정에 더 집중하는 대신 드라마틱한 전개에는 관심이 덜한 경향이 있다고 말했습니다. 이것은 미국과 한국의 공연 제작자들 사이의 문화적 차이에 대한 하나의 관점에 불과하지만, 전 세계적으로 이야기를 전달하고자 하는 사람들이 고려해야 할 관점 중 하나라고 생각합니다.

한 작품이 전 세계 관객에게 다가가기 위해서는 어떻게 해야 할까요? 예를 들어, 현재 <위대한 개츠비>는 브로드웨이에서 공연 중인 것과 브로드웨이 진출을 목표로 하는 것, 두 개의 버전이 있습니다. 한 버전은 지난달 보스턴에서 개막했는데 날카롭고 거칠며 퀴어 요소가 포함되어 있습니다. 반면 신춘수 프로듀서가 제작한 브로드웨이 버전은 국제 시장을 염두에 두고 제작된 만큼 조금 더 보편적으로 접근할 수 있는 방식으로 이야기를 전달합니다.

2. 브로드웨이로 가는 몇 가지 경로

한국 프로듀서와 창작진이 브로드웨이, 그리고 그 너머로 나아가기 위해 선택할 수 있는 다양한 전략에 대해서도 말하고 싶습니다. 경로 중 하나는 이미 <위대한 개츠비>가 채택한 것으로, 전적으로 상업적인, 이윤 추구의 경로입니다. 창작 개발 및 제작을 위한 모든 자금 조달이 상업 부문에서 이루어졌습니다. 이는 예술적으로는 조금 보수적이고, 창의적인 위험을 덜 감수하는 대신, 전 세계적으로 상업성이 높은 요소인 로맨스와 화려한 연출에 집중합니다.

한국 제작자에게는 미국 비영리 부문과의 접촉을 고려하는 것도 흥미로울 것입니다. 뉴욕과 미국 전역에 걸친 극장 네트워크는 기관, 기업, 정부(이는 급격히 감소하고 있습니다) 및 개인 기부자로부터 기부를 받아 제작 예산을 충당합니다. 많은 비영리 극장은 ‘구독자’ 혹은 ‘회원'이라는 고정 관객을 보유하고 있습니다. 한국 제작자도 이러한 비영리 극장과 협력하는 방법을 통해 공연을 선보일 수 있을 것입니다. 또, 많은 비영리 극장은 수년간 지역 사회와 교류하고 있습니다. 예를 들어 비영리 극장이 현지 아시아계 미국인 커뮤니티와 강력한 유대 관계를 맺고 있을 경우, 이들은 한국에서 온 새로운 작품을 환영해 주는 초기 팬이 될 수 있습니다.

서울과 브로드웨이 간의 협력을 촉진하는 또 다른 중요한 방법은 K-뮤지컬 국제마켓과 같은 문화 교류입니다. 이러한 행사와 KAMS가 뉴욕에서 개최하는 뮤지컬 쇼케이스는 한국의 작품 및 창작진이 브로드웨이 등 해외 시장에 소개되는 기회를 제공해 줍니다. 해외 공연 시장과 교류하려는 노력이 계속된다면 더 많은 한국 뮤지컬이 전 세계에서 자리를 잡을 수 있는 기반이 마련될 것입니다.

3. 한국과 미국의 뮤지컬 접근 방식의 차이점 : 무대 위의 관점에서

서울에서 본 공연을 기반으로 생각해 보았을 때, 한국 뮤지컬은 미국 뮤지컬에 비해 어두운 분위기의 이야기를 더 잘 받아들이는 것 같습니다. 미국 뮤지컬은 대부분 긍정적이거나 희망적인 결말을 맞습니다. 그러나 제가 본 한국 뮤지컬에서는 이러한 결말은 일반적이지 않았습니다. (심지어 로맨틱 뮤지컬인 <어쩌면 해피엔딩>에서도 그 ‘해피엔딩’은 ‘메이비’라는 조건이 붙습니다.) 한국 관계자는 한국 관객이 고난, 어려움을 중요하게 다루는 이야기를 선호한다고 말했고, 저는 미국인들도 그렇다고 답했습니다. 다만 미국 관객들은 그 고난이 극복되는 과정을 보는 것도 좋아합니다.

또한 한국 작품은 어두운 이야기를 진지하게 소화하는 반면, 미국 예술가들은 어두운 이야기를 코미디로 표현하는 경향이 있다는 것을 발견했습니다. 예를 들어, K-뮤지컬 국제마켓에서 짧은 버전으로 관람한 <배니싱>은 비극적인 오페라처럼 진지하게 이야기를 표현합니다. 서양의 창작자였다면 아마 이를 유머러스하게 표현했을 것입니다. <배니싱>은 해외 관계자들에게는 낯선 이야기와 분위기를 특징으로 하지만, 이미 한국에서 성공을 거둔 작품으로, 해외에서도 성공할 가능성이 있습니다.

마찬가지로, 초연 10주년을 맞이한 <프랑켄슈타인>은 <오페라의 유령>과 맞먹는 화려한 프로덕션으로 어두운 이야기를 표현합니다. 미국 관객인 제게 <프랑켄슈타인>은 브로드웨이에서 더 이상 찾아보기 힘든 종류의 공연처럼 느껴집니다. (제작되더라도 자주 실패하곤 합니다) 대규모 캐스트를 지닌, 진지한 대서사극 말입니다. 저는 주요 역할 배우들이 1인 2역을 맡는 이 작품의 대담함에 감탄했습니다. 이 작품이 미국에서 성공할지는 장담할 수 없지만, 이미 일본에서 공연된 바 있으며 유럽에서도 좋은 반응을 얻을 수 있는 뮤지컬입니다. 따라서 이 작품이 다른 국제 시장에서도 성공할 가능성은 충분합니다.

4. 한국과 미국의 뮤지컬 접근 방식의 차이점 : 무대 아래의 관점에서

제가 참석한 K-뮤지컬 국제마켓의 피치 세션과 일대일 회의에서, 한국의 프로듀서와 창작자들이 뮤지컬 극장 비즈니스를 ‘사업적으로’ 이야기하는 모습이 인상적이었습니다. 모든 사람들이 자신들의 프로젝트의 타겟 관객의 통계를 제시했고, 자신들의 IP에 대한 시장 조사 결과를 제공했으며, 그들의 이야기가 해외에서 성공할 수 있도록 현지화하는 방법에 대해 논의했습니다. 많은 사람들이 뮤지컬 제작의 경제적 측면에 대해 명확하게 이해하고, 이에 대해 이야기하는 것을 듣는다는 것이 신선했습니다. 이는 사람들이 급속히 확장되고 있는 아시아 시장에서 얼마나 큰 잠재력을 발견하고 있는지를 보여주는 또 다른 증거이기도 했습니다.

다른 한편으로는, ‘이 이야기를 왜 하고 싶은지’에 대해 이야기하는 사람이 거의 없다는 사실이 놀라웠습니다. 이는 프로젝트에 대한 창작진의 열정에 중점을 두는 미국 시장과는 뚜렷한 대조를 이룹니다. (그 누구도 시장 조사를 통해 <해밀턴>을 후원하지 않았습니다. 창작진은 작품에 대한 열정이 있었고, 프로듀서들은 그 작품과 사랑에 빠졌기 때문에 작품에 참여했습니다.)

피치 세션에서 ‘이 이야기는 브루클린을 배경으로 하지만 다른 어디로든 설정될 수 있습니다.’라는 말을 많이 들었습니다. 작품이 지닌 이야기의 배경을 각 국가에 맞게 설정할 수 있다는 점이 작품의 셀링 포인트로 언급된 것입니다. 그러나 그것은 작품의 비전보다는 비즈니스적인 부분에 중점을 두었다는 점에서 긍정적이지 못한 인상을 주었습니다. 누구도 대체 가능한 이야기를 원하지 않습니다. 해외 공연 관계자들은 오직 당신만이, 당신만의 방식으로 들려줄 수 있는 이야기를 원합니다.

이번 행사에서 해외 뮤지컬 업계 관계자들의 시선을 끈 작품은 <스웨그 에이지: 외쳐, 조선!>(< Swag Age: Shout Out Joseon!>)이었습니다. 이 작품은 힙합과 랩을 시조와 결합해서, 가상의 조선시대 속 시인들의 이야기를 들려줍니다. 작은 규모의 작품들 사이에서 <스웨그 에이지>는 대형 앙상블, 매력적인 멜로디, 활기찬 안무, 억압에 맞서는 ‘언더독’들의 재미있는 이야기로 기분 좋은 놀라움을 선사했습니다. 이 작품은 보편적인 주제, 캐릭터와 문화적 특수성을 결합한 완성도 높은 이야기라는 점에서 서양 프로듀서들이 한국 창작 뮤지컬에게 원하는 바를 보여주었습니다.

5. 마치며

저는 한국어를 거의 모르지만, <어쩌면 해피엔딩>은 저를 울게 만들었습니다. 이는 버려진 로봇들의 생활 시설에서 사랑을 찾는 헬퍼봇들의 근미래 로맨스에 대한 내용입니다. 다가오는 브로드웨이 프로덕션은 완전히 별개의 연출이 될 것이며, 제가 실제로 대사를 이해할 수 있게 되었을 때 이 작품에 대해 어떻게 생각할지는 알 수 없습니다. 그러나 브로드웨이 관객이 제가 작품에 대해 느낀 것처럼 이 이야기에 반응한다면 뉴욕 버전도 성공할 가능성이 있다고 생각합니다.

서울에서 시간을 보내며, 한국에서 다양한 스타일과 주제를 다루는 새로운 뮤지컬이 많이 제작되고 있다는 것을 확인할 수 있었습니다. 창의적이고 흥미로운 한국적 시각을 담은 뮤지컬이 브로드웨이에서 큰 성공을 거두고 전 세계 관객을 사로잡을 날이 올 것이라고 생각합니다. 저는 그런 일이 일어날 것이라고 확신하며, 그런 작품을 보게 될 날을 기대합니다.

▲원문

Back in November when I wrote the headline “K-Musicals Are Coming For Broadway,” I didn’t know it would happen quite so quickly. By then it had become obvious that South Korea’s bustling musical theater industry was poised to make an international splash — that was why I dedicated one of the first issues of my newsletter about international theater, Jaques, to a detailed primer on the ins and outs of the market — but I wouldn’t have predicted that now, barely nine months later, the Korean Broadway wave looks like it’s already begun.

Not long after I wrote that piece, The Great Gatsby — a new, English-language musical produced by Chunsoo Shin of the busy, Seoul-based production company OD Company — orchestrated a swift move to Broadway, where the show opened in April and has grossed more than $1 million (USD) almost every week since then. The following month, Maybe Happy Ending, a musical created by a Korean writer and an American composer, announced it would arrive on Broadway this fall in an English-language production starring Emmy Award winner Darren Criss.

It felt like fortuitous timing, then, for me to have the opportunity to get an in-person glimpse of what’s happening in Seoul. Late last month, the Korea Arts Management Service (KAMS) held its annual K-Musical Market (June 18-22), and I was there.

This year creators, producers, executives and journalists from eight countries attended lectures and panels about theater markets around the world; heard from artists and producers about projects pitched toward international life; met one-on-one with delegates from the Korean industry; and attended a series of 50-minute performance excerpts of eight new and developing Korean musicals. As a New York-based journalist who has been writing about Broadway for more than 20 years, I was asked to give a presentation about current trends in the U.S. theater business, and how I imagine the partnership between the Korean industry and Broadway might continue to expand.

I was a first-time visitor to Seoul, and for me the conference was a fascinating experience — one that galvanized the participants with excitement about the potential for international collaboration, and also served as an illuminating reminder both of how much we all have in common and how different we are culturally, creatively and economically. After the conference ended, I stayed in town for a bit and caught performances of two notable, homegrown musical titles now running in Seoul: Frankenstein and Maybe Happy Ending.

The whole visit afforded me an informative snapshot of how the Korean musical theater market relates to Broadway. Here are some of the biggest insights I learned during my trip.

1. THE KOREAN MUSICAL THEATER MARKET IS ALREADY GROWING AROUND THE WORLD

In my conference presentation, I was asked to speak about my thoughts about the ways that the South Korean musical industry could expand its influence around the world and export a musical with the same success that your country’s entertainment industry has found with movies like Parasite, or TV shows like Squid Game, or music acts like BTS.

The first thing I would say is: It’s already happening.

The Great Gatsby is a big step forward, in terms of raising the Broadway profile of the Korean musical theater industry and the ambition of Korean professionals in the theater. And then there’s Maybe Happy Ending, which premiered in Seoul in 2016 and is playing a return engagement there now. Whereas Gatsby feels like a big step forward on the business side, Maybe Happy Ending feels significant as a creative product from a truly cross-cultural creative team, one that combines Korean and American artistic sensibilities. If it succeeds on Broadway, it’s going to get a lot more people — both in the American theater industry and beyond — interested in the work and the artists coming out of Korea.

For shows like these, one of the biggest challenges in telling stories across borders is figuring out how to shape these stories for a global audience. Every culture has different expectations for what it wants from a story and how it expects a story to be told. In an interview I conducted in New York, a young Korean American director told me that she thought that in America, audiences seem to value shows that are more plot driven and focused on a hero’s journey, whereas Korean audiences are more open to living in a feeling, and less focused on a big dramatic arc.

That’s just one point of view on the cultural differences between American and Korean theater makers, but I think it’s an indicator of the kind of thinking that people will have to do as they set out to tell their stories around the world. How might a show’s storytelling be unfamiliar to an international audience, and in what ways can the show make that story as accessible as it can be around the world?

It’s instructive, I believe, to think about The Great Gatsby, which is one of two musical versions of the same story that are on Broadway or aimed at Broadway. The other version, which just opened in Boston last month, is a lot edgier and grittier and incorporates more queer elements than the version that is produced by Mr. Shin and OD Company on Broadway. I think it’s not accidental that in the latter version, the one produced with a clear eye for the international market, many of the choices are more universally accessible across cultures. It tells the story from a perspective that could travel well.

2. SOME POSSIBLE PATHS TO BROADWAY

I also want to mention some of the different strategies that Korean producers and Korean could embrace in order to expand their work to Broadway and beyond.

One of these paths has already been taken by The Great Gatsby: That’s the fully commercial, for-profit route. All of the fundraising for its creative development and production has been done entirely within the commercial sector. It’s perhaps artistically a little more on the conservative side, and take fewer creative risks, but instead it focuses on some of the elements that often sell well around the world: romance and razzle-dazzle spectacle.

For Korean producers or artists, it also might be interesting to explore connections with the American non-profit sector. This is a network of theaters, in New York and around the country, that are similar to what are called subsidized theaters in the U.K. For these organizations, their production budgets, and indeed all of their funding, comes from charitable donations from institutions, from corporations, from the government (although that’s rapidly decreasing), and from individual donors.

A lot of these non-profit theaters have what we call “subscribers” or “members,” who are built-in audiences for the organization’s shows. For Korean producers and artists, working with such an institution could provide an accessible American audience for a trial run. In addition, a lot of not-for-profit theaters in the U.S. have worked hard over the years to build connections in their community and might, for instance, have strong ties to a local Asian American community that could become early enthusiasts for a new show coming over from Seoul.

Another important way to encourage collaboration between Seoul and Broadway is through cultural exchange like the KAMS conference. I know that this annual event, and the showcases of new work that KAMS holds in New York, are important ways that Korean talent, Korean producers and Korean shows are introduced to the Broadway industry and to other Western markets. Additional efforts to make connections with people in the global theater industry will continue to lay the groundwork for more and more Korean musicals to find homes around the world.

3. THE KOREAN VS. THE AMERICAN APPROACH TO THE THEATER BUSINESS: THE BIGGEST DIFFERENCES I OBSERVED ONSTAGE

Judging from the show excerpts and full productions that I saw in Seoul, it seems to me that the stories told in Korean musicals embrace darker themes than the stories common to American musicals. Or perhaps more accurately: Most American musicals have happy endings, or at least offer final notes of upbeat hope or pleasure. That was a lot less common to the Korean musicals I saw. (Even in the sweetly romantic Maybe Happy Ending, that happy ending comes with a maybe attached.) One local told me that Koreans like stories that prominently feature hardships; I told her that Americans do too; it’s just that we also like it when those hardships are overcome.

I also found that Koreans embrace dark, Gothic stories told in a very serious tone — whereas American artists would be more inclined to play these dark fantasies for comedy. For example: The vampire story Vanishing, of which I saw an excerpt, tells its story with the seriousness of a tragic opera; a Western creator would probably be inclined toward camp or humor. Vanishing featured a pairing of narrative and tone that the conference’s Western delegates couldn’t imagine working in their markets — but it’s a show that’s already had some success in Seoul, and stands poised for life abroad.

Similarly, Frankenstein, the successful K-musical now celebrating the 10th anniversary of its premiere, tells an epic story of dark grandeur, in a lavish production that would rival The Phantom of the Opera. To an American theatergoer like me, Frankenstein feels like the kind of show that just doesn’t get produced on Broadway anymore (and when it does, it often sputters): a sweeping, expensive period saga with a big cast and a serious, grandiose tone.

Still, I admired the conceptual daring of the show, which sees each of its six major actors double-cast in surprising roles. And even if I can’t imagine the show becoming a success in the U.S., it has already played Japan and seems like the kind of musical that could also do well in Europe — so there is still plenty of potential for the show to be embraced in other international markets.

4. THE KOREAN VS. THE AMERICAN APPROACH TO THE THEATER INDUSTRY: THE BIGGEST DIFFERENCES I SAW BEHIND THE SCENES

In the full-group pitch sessions and one-on-one meetings I attended, it was striking how often Korean producers and creators talked about the musical theater business like it was just that—a business. Every artist could give you a demographic spread of the audience that their project was expected to appeal to, provide promising market research on their choice of IP, and talk through all the ways their story could be localized for maximum success abroad.

On the one hand, it was refreshing to hear so many people talk about theater with such a clear-eyed understanding of the economic side of making musicals. It was also another indication of how much potential people see in these rapidly expanding markets in Asia and beyond.

On the other hand, for me and for other Westerners in the audience it came as a real surprise how little anyone talked about creative inspiration and why they were driven to tell their particular story. It seemed a stark contrast to the American theater business, where the economics are such a crapshoot that usually the emphasis is on artists and their passion for a project. (No one got behind Hamilton because of market research, which would never have predicted that show’s success. The artists pursued it because they were passionate about it, and producers got involved because they fell in love with the project.)

In these pitch sessions, we heard a lot of “This story is set in Brooklyn, but it could be set anywhere.” It was presented as a selling point — you can tailor this story specifically to your audience and your territory! — but for this American (and Brooklyn resident), it was an off-putting mark of a story led by business considerations rather than creative vision. Among my fellow delegates from the U.S. and U.K. who specialize in new work, no one wants interchangeability. They want a compelling story that only you can tell, in the way that only you would tell it.

For the conference’s Western delegates, the standout show was Swag Age: Shout Out Joseon!, which pairs hip-hop and rap with sijo to tell the story of rebel poets in an imaginary version of the Joseon Dynasty. Among a slate of shows focused on small casts and modestly scaled productions, Swag Age was a delightful surprise with a large ensemble, catchy tunes, lively choreography and an entertaining storyline about underdogs fighting oppression with poetry slams.

Swag Age exemplified what many Western theater producers would look for in a Korean-born show: a fun, high-concept story that pairs real cultural specificity with universal themes and characters.

5. ONE FINAL THOUGHT

I know very little Korean, but Maybe Happy Ending still made me cry. It helped that I did a quick pre-curtain read of the musical’s extremely thorough Wikipedia summary, which ran down the basics of this sweet, near-future romance about helper-bots finding love in a living facility for abandoned androids.

The upcoming Broadway production will be an entirely separate staging, and who knows what I’ll think of the show when I can understand the actual words. But judging from what I saw, the New York version just might succeed if Broadway audiences respond to the story the way I did.

During my time in Seoul, it became clear to me that there are so many new Korean musicals being made, in such a variety of styles and subject matter, that I think it’s only a matter of time before a new, Korean-born musical, showcasing an imaginative and exciting Korean perspective on an ingenious story, is going become a big Broadway success and attract audiences around the world. I feel sure it’s going to happen, and I can’t wait to see that show.